Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 18, No. 1 (2020)

The Benefits and Limitations of Online Peer Feedback: Instructors’ Perception of a Regional Campus Online Writing Lab

Ana Wetzl

Kent State University at Trumbull

awetzl@kent.edu

Pam Lieske

Kent State University at Trumbull

plieske@kent.edu

Abstract

The socioeconomics of the working-class area where our open- admission regional campus is situated have resulted in a struggle to prepare and retain our underprepared students. The campus tutoring center is central to our retention efforts; to address the needs of our population, we offer both face-to-face and online tutoring. The article reports the findings of an empirical study that looks at writing instructors’ perception of these tutoring services, with emphasis on the online component. The study reveals the participants’ preference for online versus face-to-face tutoring, which has been driven by their students’ socioeconomic characteristics. It also shows a clear preference for the campus online tutoring service that is favored by our instructors over eTutoring, a tutoring service serving students from many Ohio universities. Despite their support for the campus- based online tutoring, our participants pointed out several areas of improvement, such as the need to focus more on higher-order concerns and to address the delays in tutor response. The research emphasizes the need for more tutor training and, more importantly, more resources to be directed toward campus-based online tutoring services.

As universities increasingly embrace online instruction, tutoring centers find themselves having to respond to the needs of remote students. Our¹ university, which consists of a main and seven regional campuses, has three online writing labs (OWLS): one at the main campus, one at a large regional campus, and one at our small regional campus, which has been operating the T. OWL since the early 1990s. Additionally, our students have access to eTutoring, a service provided by a consortium of Ohio universities that employs both students and post-graduation professionals. Our students are indeed fortunate to have several tutoring options, and we both recommend or require them to use the online labs. We wonder, however, whether other professors from our campus share the same enthusiasm about these tutoring options, particularly about our T. OWL. At the end of the Spring 2019 semester, we used an online survey to inquire into our colleagues’ perception of various tutoring options, including the face-to-face services provided by our campus tutoring center. We were surprised to see that our research participants not only embraced online tutoring as a way to respond to the particularities of our student population, but they also showed a clear preference for our T. OWL. While they considered eTutoring an option for students looking for more perspectives on their writing, they nonetheless valued T. OWL more because they were familiar with how the T. OWL operates as well as the institutional knowledge our T. OWL tutors draw from when providing feedback to their tutees.

The result of our research follows. We first describe our student population and the tutoring services offered by our small regional campus. Next, we review the challenges that come with tutoring underprepared students, especially when tutoring happens asynchronously online. We then discuss our instructors’ perception of the tutoring services provided by our online tutors. While some of what we learned about online tutoring from our instructors is specific to our campus, other conclusions and insights are universal and can be adapted to other institutions. The research is particularly timely as universities consider extending online instruction through fall 2020 and beyond in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our hope is that this article helps teachers think through how and in what ways online tutoring can be used in their classroom while it also provides writing and learning center professionals an opportunity to consider and reflect upon the challenges and rewards that come with offering online tutoring services.

Background INformation

Our Students: Under-resourced and Underprepared

Before we discuss the data provided by our research, we need to explain the most important reason why we prefer online over face-to-face tutoring: our student population is both severely under-resourced and underprepared both in terms of material resources and time, and makes driving to the campus for tutoring rather difficult. Our campus serves both rural areas in Northeast Ohio and urban centers in Warren, Ohio, located half a mile from the campus, and Youngstown, Ohio, approximately twenty minutes away. Both rural and urban families used to enjoy the economic and social benefits that came with a booming steel and car industry, but the area has been on a continuous downward slope since the late 1970s. After the first massive layoff, known as “Black Monday,” that occurred on September 19, 1977, over 22 steel mills closed in the next twenty years, impacting other industries and all aspects of residents’ lives. The recently closed General Motors plant just a few miles away from our campus represents the latest of numerous manufacturing closures that have resulted in brain drain, as our educated residents have been forced to relocate for better opportunities elsewhere, leaving behind low- wage employment that does not require a college degree (Linken and Russo). According to the 2017 Census, the median household income for the urban area near our campus is $29,241, and only 13.6 percent of residents holds a bachelor’s degree or higher.

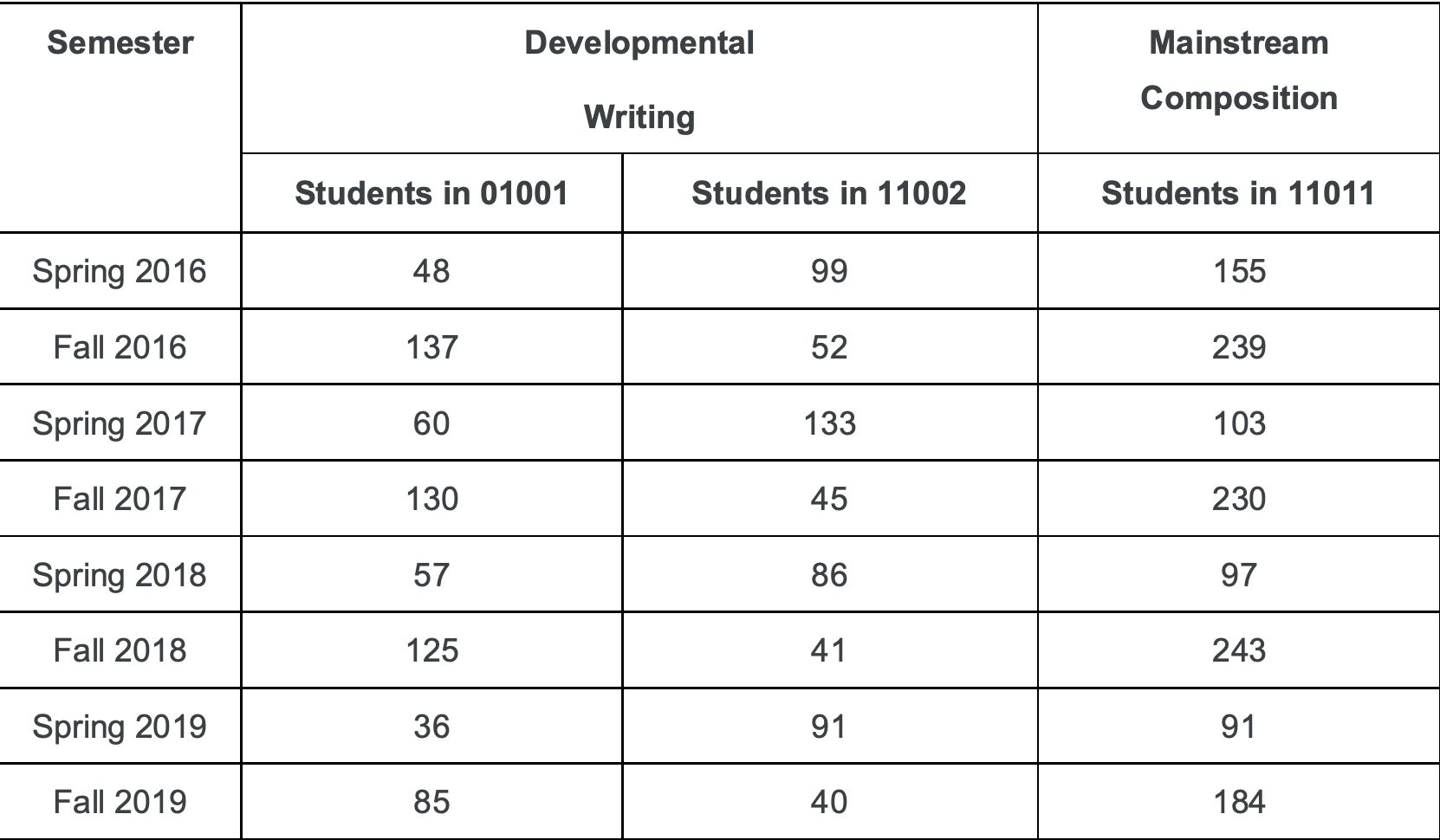

The loss of revenue and the brain drain have also altered the quality of education provided by the local schools. Warren’s and Youngstown’s public schools have mirrored the downward spiral of the local industry as they are currently rated F for academic preparedness for college and rarely see a rating higher than D (Ohio Dept. of Ed., “Youngstown”; Ohio Dept. of Ed., “Warren City”) Additionally, the Youngstown public school district has been in academic emergency since 2010 (Ohio Dept. of Ed., “Youngstown”). With such deplorable secondary education, it is no wonder that the students who enroll at our open-admission campus end up placing in developmental courses. Most semesters, almost half of the students taking composition at our campus are placed in English 01001 and English 11002, the first and second semester developmental writing course, respectively. These two courses make up the developmental writing equivalent of English 11011, our mainstream first year writing course. Table 1 (See Appendix A) provides the enrollment data for English 11011 and English 01001 and 11002 As seen in Table 1 many of our students are not prepared to take regular college writing courses. Additionally, we noticed that many of our students had to take the first developmental writing course multiple times before they could pass it, while others never completed the course and dropped out. This further emphasizes the lack of academic preparedness affecting our student population.

Our Tutoring Services

Considering that most of our students come underprepared, they need more support from knowledgeable peers than the average American student. Recognizing the challenges of educating this population and, again, ever mindful of retention, our campus has several services in place to assist students including the Learning Center whose primary task is to support students academically outside of class. Staffed by undergraduates, graduates, and faculty, the Center offers a quiet study area and face-to-face and online tutoring. In the last ten years, we have employed as many as nine and as few as four English tutors each term. This varies depending on the number of hours assigned to each tutor, but the goal is to have complete coverage for English tutoring during our business hours (Monday- Thursday 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. and Friday 9 a.m. to 3 p.m.). Some of our tutors are graduate students, but most are undergraduates from a variety of majors. In spring 2019, for example, our tutors were undergraduates majoring in English (four tutors), Business (one tutor), and Nursing (one tutor). This variation in the tutors’ academic interests represents one of the strengths of the program because it makes feedback less homogenous. Our tutors are all strong writers who come with excellent recommendations from campus professors and boast high GPAs (“Learning Center Employment”).

Students requesting electronic tutoring submit their papers using an online form linked to a listserv that instantly distributes the submission to the English Coordinator and the English tutors. The first available English tutor then takes the submission, reviews it, provides suggestions for revision, and sends the paper back to the tutee. This cycle can take up to forty-eight hours although most essays are reviewed more quickly; however, during key points in a term, such as near midterms or finals week, the response time may be lengthened slightly. Next, the tutee may choose to revise and resubmit the paper to be reviewed a second time by a tutor. This tutoring cycle can continue until the tutee is satisfied. In this way, the T. OWL largely mirrors what occurs with other tutoring services such as eTutoring where students may submit the same paper, in varying stages of completion, up to three times for feedback, although there is no such limit for T. OWL. The difference is that given the size of its organization, eTutoring students may receive feedback from three different tutors while the same T. OWL tutor often reviews the same paper again and again.

Tutoring Underprepared Students

Getting our students to use the Learning Center can be a struggle for various reasons ranging from the desire to be self-reliant that is characteristic of Rust Belt communities to the lack of familiarity with the concept of tutoring, as the local high schools do not have learning or writing centers. Our campus professors, however, are our allies in the struggle to match our struggling writers with a tutor. This is why instructors’ perspective on online tutoring is particularly relevant because they are instrumental in their students’ decision to seek tutoring. Recently, Wendy Pfregner et al. collected longitudinal data from another regional campus at our university where they followed 349 remedial student writers whose instructors were committed to making tutoring part of the writing process. Pfregner et al. found that students who were required to visit their campus’s writing center were more likely to “pass their second-semester writing course (69.4% versus 79.6%) and less likely to withdraw (14% versus 8.5%)” than students who were not required to seek tutoring; moreover, students who frequented the writing center in their first semester tended to visit in subsequent semesters (Pfrenger et al. 24-5). Pfrenger et al.asserted that students’ repeat visits to a campus writing or learning center “shifts educational attitudes and behaviors in advantageous ways” (26). In other words, making the Learning Center part of these students’ writing process not only results in a better grade for that specific paper, but it leads to more profound changes in how students perceive their college experience.

Working with tutors in a comfortable environment helps students develop writing skills and gain confidence in their academic abilities—t hings sorely lacking in all beginning college writers but especially in remedial writers such as ours. In his report on the impact of learning assistance centers on community college students’ success, Keith Wurtz speaks to this point. He states that “fifty-four percent of entering community college students” are not college ready, much like our regional campus students who end up enrolling in remedial writing courses, yet these same “students are three times more likely to successfully complete their course if they obtain help for the course in an LAC [Learning Assistance Center] and two times more likely to persist to the subsequent term” (Wurtz 2, 6). Clearly, the impact of face-to-face and online tutoring continues even after the course ends and can be a tool used in the fight for retention.

Moreover, working with a peer writing tutor gives students the benefit of working with an expert without the pressure of having to interact with the course instructor. While it may be difficult for writing teachers to hear this, “in practice, instructor feedback, particularly written feedback, is often ineffective, especially when instructors are overwhelmed by the demanding nature of writing assignments” (Cho and MacArthur 329). Vague, directive, and even canned responses that are not specific to a student’s paper may be the result as well as an over attention to surface errors like punctuation and formatting. Student reviewers, on the other hand, tend to “use the same language [as their peers] without using professional jargon” and “share similar knowledge, language, and experiences” (Cho and MacArthur 329). As a result, the tutors and the tutees communicate with each other in ways that writing students and their instructors often do not. In a large- scale study of 708 students across sixteen disciplines, Kwangsu Cho et al. found that when at least four carefully trained peer reviewers assessed a piece of student writing, “the reliability and validity of peer reviews” was comparable to that provided by an instructor (891, 898). Peer or student feedback is also often more concise and positive in nature than that generated by writing teachers, and “non-directive feedback [by peers] might be associated with greater psychological safety” (Topping 342). Peer feedback certainly supports the development of writing skills and can be done well when tutors are involved. In their survey of the research on peer review, Kwangsu Cho and Charles MacArthur claim that though research on the topic is limited, “peer revising is . . . generally positive” (328).

We understand how important it is for our students to hear a peer’s feedback, which is why we organize in- class peer reviews. At the same time, however, we have noticed that our students often struggle to provide useful reviews because they are underprepared themselves and thus hesitant to express an opinion when they do not feel like an authority. Consequently, a tutor’s feedback may be more beneficial for a student whose in-class peer reviewer may have limited writing skills. For instance, our students tend to focus more on obvious lower order concerns such as format and grammar, and forgo more relevant concerns such as critical thinking, writing cohesive paragraphs, thesis development, and citation. Our tutors, however, are coached by the English Coordinator to focus on higher order concerns; this occurs both during the initial post- hire one-on-one training, and in the group training that occurs twice a semester. During these sessions, tutors receive training about best practices in face-to-face and online tutoring and discuss the rubrics that our professors use to assess our students’ writing. For instance, the rubric for assessing the end-of-semester portfolio in English 01001 recognizes the importance of good command of the English language, but it puts significantly higher emphasis on higher order concerns such as developing a central idea and providing evidence for claims (Appendix B). The most important tutor training occurs during the first week of the semester when the tutors and the coordinator spend four hours discussing face-to-face and online tutoring. The second training occurs right after midterms and focuses on problem-solving regarding specific papers or tutees they have encountered. Because both training sessions are held in a group setting, tutors are provided the opportunity to reflect on and learn from their own and one another’s work.

In addition to offering a certain degree of expertise when it comes to writing, the tutors can also rely on the institutional knowledge they have developed from being students and Learning Center staff. Because of the campus’s small size, most tutors have worked with their tutees’ professors, and even if they have not taken a class with a particular instructor, fellow tutors likely inform them about the types of prompts and papers a specific writing professor requires. With only fourteen full-time and adjunct English instructors, it is not difficult for tutors to gain information about their tutees’ primary audience, i.e. their professors. Moreover, our Learning Center is a social and academic hub for students and tutors; students go there to do their homework, and tutors from all disciplines can often be seen socializing during down time. When a student comes in for assistance, a tutor may move to a quieter location near a row of computers to work, but that sense of community and solidarity remains, and, as suggested above, our campus writing tutors have unique knowledge of a professor’s writing pedagogy, personality, and grading habits. This allows tutors to communicate “inside” knowledge directly to their tutees; moreover, if the tutor was a previous student of a professor, he or she is even more acutely aware of the context and challenges under which the tutees write.

Student Population and Online Tutoring

Our students can visit the campus Learning Center for a drop-in face-to-face session, but access is a problem because spending extra time on campus to work with a tutor may not be an option for our population. Many students are older adults coming back to complete their education while also working and raising a family; younger students are equally as busy with most of them holding part-time and even full-time jobs, which means they may not have the time to visit the Learning Center. The campus has also welcomed College Credit Plus (CCP) students who want to complete their college composition requirements while they are still in high school or even junior high. Some CCP composition courses are held at the local high school, which means that the students have little motivation to set foot on our campus, let alone the Learning Center.

Additionally, some of our students prefer online courses and are seldom, if ever, on campus. Online composition courses are quite popular with our students; in the fall of 2019, our university system offered fifteen online sections of English 11011, the first semester freshman composition course, each with a cap of 19. There was only one open seat across all online sections by the time of the drop date. During the same year, our university also offered twenty-six online sections of second semester freshman composition, English 21011, with only six open seats remaining at the time of the drop date. This means that 770 students chose to take an online freshman composition course (“Schedule of Courses”). This is a jaw-dropping number and works to show just how popular online writing classes are at our university. Online instruction is now more relevant than ever considering the campus shut down in mid-March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 virus and continues to be closed at least until the fall 2020 semester.

As the university increased the online and CCP course offerings in the last six years, we noticed a spike in the number of submissions to the T. OWL. When Joe Dudley created the T-OWL in the early 1990s, the Learning Center handled only a handful of online submissions each semester. This changed in the last four years. Between the beginning of the spring 2017 and the end of the spring 2019 semesters, the Learning Center received 586 online submissions (“OWL Submissions Report”), a significant number for a campus with only a little over 2200 students (“Facts & Figures”). Moreover, the increase in submissions continues to accelerate. In Spring 2018, the Learning Center received 67 online tutoring requests; that number almost doubled in Spring 2019 to 120, and it is climbing even higher as a result of the COVID-related campus closure. Even the number of summer session submissions doubled from 19 in Summer 2018 to 52 in Summer 2019.

Challenges for Our T-OWL

The high demand in online tutoring means that the number of OWLs has caught up with the number of face-to-face sessions, but we still find ourselves putting the needs of our online tutees on the back burner. The Learning Center does not require appointments for either form of tutoring, so it cannot anticipate the need for either on a specific day. Tutors are trained to give precedence to tutees who physically come to the center for help over those who submit their essays electronically. We choose to delay reviewing an OWL rather than to turn away a student who walks into the Learning Center because we understand how difficult it is for our population to find the time for a face-to-face session. Moreover, new hires are not required to participate in OWL tutoring during their first semester in the Learning Center because they first observe more experienced tutors when they review OWLs, and they undergo one-on-one training with the Learning Center English Coordinator. This means that only more experienced tutors can review OWLs, and since they review submissions in between face-to-face sessions; often submission may not be reviewed until the day after or even later. The goal should be to assist all writing students equally and in a timely manner, but students who ask for feedback electronically may be at a disadvantage both in terms of how readily they receive feedback as well as the quality of feedback provided. After all, tutors who rush to complete OWLs at the end of the day, or when they have a few minutes in between tutee sessions, may not be providing the best feedback. There are also ethical issues emerging from online tutoring. The peer feedback we provide in the Learning Center for both face-to-face and online tutoring is directed by the tutees, and tutors are always trained to follow their lead. This is important as it would be unethical for a tutor to take charge of a tutee’s paper. As Peter Carino explains, writing centers’ endorsement of nondirective peer feedback and collaborative learning originated as a response to charges of plagiarism or over-editing by tutors as well as the fact that writing centers sit on the bottom of the academic hierarchy without “academic status” and without any formal role in instruction (96-102). Carino goes on to praise nondirective questioning by tutors to their tutees, claiming that “nondirective tutoring can cue students to recall knowledge they have and construct new knowledge that they do not” (103). Cultivating an atmosphere of positive, nondirected feedback and open communication is the primary aim of the T. OWL, as we attempt to replicate in the online environment what transpires in a face-to-face setting.

However, providing nondirective feedback is particularly challenging in online settings where the tutor-tutee dialogue is limited. To aide with this issue, we require our tutees to complete a submission form to inform the peer tutor of their main concerns for the paper. The form includes a checklist with various writing issues such as organization, thesis development, or plagiarism, and tutees are obligated to address the higher order or lower order concerns that the tutees list. Additionally, while tutees are advised to share the writing prompt and any feedback by their professor with the peer tutor, it can still be difficult for tutors to ask questions and open a dialogue that answers the tutees’ and the professors’ concerns.

Our Research Study: Instructors’ Perception of T. OWL

We rely on the professors’ support to get students to use our Learning Center services, including the OWL, so their perception of the OWL’s effectiveness is important. Up until the end of the Spring 2019 semester, there was no process in place to receive feedback from instructors regarding the Learning Center. The only times the English Coordinator would hear from a professor was when problems occurred, such as when there was a delay in the tutor’s response to a specific paper, or when a professor saw and did not like a tutor’s written response to one of his or her student’s papers. After the conclusion of the spring 2019 semester, however, we decided to survey our full time and part- time instructors using an anonymous online questionnaire about our tutoring services (See Appendix C). We collected a mix of quantitative and qualitative data, mostly about the T. OWL. Eight out of the twelve instructors invited to participate in the study completed the survey. Most of the participants have extensive experience delivering writing courses, with four instructors having taught for more than seven years at our campus. Only one participant had under two years of teaching for us.

The Results of our study

Online Tutoring Gains Ground against its Face-to-face Equivalent

The most interesting finding emerging from the study is the instructors’ preference for online over face- to-face tutoring. We anticipated that the participants would prefer the more traditional face-to-face tutoring because of the benefits that come with its synchronous nature such as the immediacy of tutor feedback and the tutee’s ability to ask and answer questions. According to the survey data, however, all eight participants reported that they recommended online tutoring to their students, while only five of them also mentioned face- to-face tutoring. This may come as a surprise considering that our university has more opportunities for face-to-face tutoring as all eight campuses offer it, while only three provide OWL assistance. However, the student population and the type of courses in which they are enrolled may explain the preference for online tutoring. Three of the instructors surveyed taught online courses, and another three taught their face-to-face college writing courses in a high school classroom often miles away from our campus. Considering how difficult it would be for these students to access face-to-face help due to location, it makes sense that the instructors would recommend online tutoring. Online courses, after all, appeal to students who need flexibility and cannot generally travel to the campus.

While the participants in the study preferred online to face-to-face tutoring, they all seemed to choose the T. OWL over eTutoring. In fact, only one of the participants recommended or required the students to use eTutoring. This may be the result of the instructors’ familiarity with the campus English Coordinator and the tutoring staff handling OWLs; some of the professors had the tutors in their course and may even have recommended them for Learning Center employment. In contrast, submissions sent to eTutoring are read and reviewed by unknown tutors residing in unknown locations, though, to be fair, eTutoring has recently tried to hire at least one eTutor from each campus with which it is affiliated; our campus, for instance, contributes with a Science tutor. Yet, the tutor reviewing our students’ papers is not from their home campus and may not understand the context in which these students write. There is also a degree of accountability with the T. OWL that is not present with a remote service such as eTutoring; the professors know exactly whom to talk to when they want to inquire into a particular tutoring session, and at times the Learning Center English coordinator adjusts tutor training based on feedback from instructors.

It is also possible that the instructors surveyed for this study are not fully informed about the services available from eTutoring while they hear about the T. OWL through emails, course visits, and in English department meetings. Unless they take it upon themselves to keep up with the changes in eTutoring services, it is unlikely that they would know, for instance, that eTutoring has grown to a consortium of forty-three Ohio colleges and universities in 2019, up from fifteen in 2010, and that it now offers a live chat feature where students can ask tutors in real-time specific questions related to their writing (“Ohio Launches”; “eTutoring”). While the goal of eTutoring is to make free tutoring of writing and other subjects available to all college students across Ohio, it is important to note that availability and utilization are two different things. Unfortunately, statistics on student use of any of eTutoring’s services is not available online and could not be obtained through email inquiries, so it is impossible to know exactly how many writing students actually use it. Reliability is another concern to consider. During a two-month period in the summer of 2019, eTutoring stopped receiving submissions only to resume service on August 26th (“eTutoring”). If instructors and students are not certain that an online tutoring service is available, particularly a more big-box tutoring service like eTutoring, they likely will turn to their local writing or learning center for assistance.

The chat option that eTutoring recently launched is, however, an intriguing development because it offers the tutees a way to ask questions and take charge of the tutoring session. We have learned, though, that even when synchronous/live online tutoring is available, students may not use it. As previously stated, in addition to the T. OWL, there are two other tutoring centers at our university that offer both face-to-face and online tutoring. One of them also has a live chat feature, but Jeanne Smith, the director of the tutoring center at our university’s main campus, states that the “chat is used fairly infrequently, historically making up less than 10 %” of tutoring sessions.” We also tried offering chat tutoring on our campus during the last eight weeks of the spring 2020 semester, but there were no inquiries on the part of the students who preferred to submit their paper to the asynchronous T. OWL instead. This is hardly surprising; as we saw with the T. OWL, it can take years, and sometimes even decades, for our students to embrace new technology.

While regular advertisement of our campus’s online writing lab may have impacted our participants’ decision to send their students to T. OWL, the most important reason why this is preferred over eTutoring may be the institutional knowledge that comes from tutors and tutees sharing the same space. The campus tutors may have a better understanding of what a tutee needs based on their previous experience tutoring students taking the same course or a similar course with the professor. It is not unusual to walk by a tutor busy with an OWL submission and hear her mumble to herself: “All right.... it’s a paper for Professor L. Let’s see the thesis. Ummm. This will not work. I’d better tell the tutee to revise this three-point thesis. I know L. does not like that.” This institutional knowledge is passed from one tutor to another during the first group training of the semester when the tutors have approximately one hour to share their observations about tutoring during the previous semester. A similar discussion occurs during the mid-semester group training as well. Additionally, the tutors help one another with the OWLs. On Monday afternoons during the Spring 2019 semester, for instance, the two English tutors on the schedule shared the same table as they both reviewed OWLs, exchanging occasional comments and asking each another questions. These conversations allowed the tutors to tailor their feedback not only to meet the tutee’s expressed needs, but to what they knew the professor valued as well. It would be difficult for the eTutoring staff to duplicate this kind of knowledge considering that they work independently and serve students from many Ohio universities.

OWL Feedback Problems: Focus on Lower Order Concerns

Although it was clear that all instructors who participated in the study valued the T. OWL, they nonetheless emphasized the need to see a shift in the tutors’ feedback. Four out of the eight participants were concerned about the tutors’ tendency to focus on lower order concerns and brought up what one called a “lack of substantive feedback” that they had noticed in the tutors’ reviews in addition to their tendency to address lower order concerns, particularly grammar. When asked what aspects of their students’ writing they wanted the tutors to address, instructors focused mostly on the quality of the content and the way the paper was organized, listing issues such as thesis development and organization, with only two instructors pointing to lower order concerns such as grammar. Considering the instructors’ focus on higher order concerns, it makes sense that they were unhappy to see the tutors commenting on grammar mistakes in their feedback.

Our online tutors’ excessive focus on lower order concerns is not new and has been documented in a 2015 conference paper written by four out of the seven tutors employed by the Learning Center at the time. Stephanie Gotti et al. set out to understand the type of feedback tutees receive when they submit their papers to our T. OWL. For this empirical study, the tutors randomly selected twenty student papers submitted in the first half of the fall 2015 term, and they looked at whether the feedback provided targeted lower or higher order concerns. Findings showed that most comments peer tutors gave to tutees focused on mechanics, with only a smattering of comments focused on content and argument development (Gotti et al.). Specifically, forty- two percent, or 186 out of 440 comments, were comments pointing out mistakes in grammar, punctuation, and spelling (Gotti et al.). The findings of the Gotti et al. study anticipate our participants’ concerns four years later and suggest that additional tutor training may be warranted.

What could be causing this focus on lower order concerns? It may have resulted from several factors including the tutees’ tendency to directly ask for feedback about grammar, spelling, and punctuation when they submit their papers. It seems like there is a disconnect between what professors deem important and what the tutees think their professors want them to do; the instructors participating in our research study were aware of it. When we asked them to share their expectations for a tutoring session, one of them wrote: “I am hoping for higher order concerns such as organization, thesis, expert use of sources. Unfortunately, most students end up just with a proofread paper. I am guessing that it is because that is what my students ask for.” This aligns with results from another study done by Laurel Raymond and Zarah Quinn who found that “writers visiting . . . [their] center tended to request attention to more sentence-level concerns” than attention to “larger-level concerns’ like argument (73). Between the beginning of the Spring 2017 and the end of Spring 2019 semesters, our T. OWL received 433 requests for help with grammar/punctuation/spelling, and only 239 students asked for help with the thesis statement (“OWL Submissions Report”). Chart 1 (See Appendix A) shows the concerns that the tutees expressed when they submitted their paper to be reviewed by an OWL tutor.

Tutees’ concerns with surface errors highlights the limitations of asynchronous online tutoring. In face-to- face tutoring sessions, our tutors are trained to spend the first few minutes of the session clarifying with the tutee what issues carry more weight when drafting and revising, but there is no easy way to educate tutees about higher order concerns when responding to OWL submissions. The linear nature of the feedback provided during the online tutoring session prevents or makes difficult any dialogue with the tutee, and therefore the tutor has no opportunity to check the tutees’ comprehension of revision needs, or to explain to the tutee what aspects of the paper are more important than others. In addition, research shows the limited interactions specific to online tutoring makes it difficult to build the rapport that helps student writers feel safe and valued, which is instrumental in making the exchange between tutor and tutee meaningful. As Joseph McLuckie and Keith Topping explain, rapport between student and tutor makes it more likely for student writers to ask clarifying questions on the feedback provided to them—again, a difficult feat if students and tutors are exchanging information in a linear, asynchronous fashion.

We also know that many tutees often lack the ability to recognize what problems their papers have and what needs to be revised. Lindsey Jesnek explains that “many freshman and sophomore students who enter lower level composition classrooms do not have a clear idea of what is expected in their writing, nor do they have a clear sense of what to look for in the revision of their own writing” (21). As a result, they may not know what to ask to work on in a tutoring session and/or request assistance with what seems easiest: grammar. According to Raymond and Quinn, writing “tutors are often faced with the difficult task of integrating tutor and writer goals; they must focus their sessions in ways that fulfill the students’ requests for the paper at hand while maintaining an emphasis on facilitating the long-term development of the writer” (65). In other words, they have to determine, without back and forth interaction, how to provide suggestions that can lead to immediate revisions and long-term learning about writing. Unfortunately, the feedback given may end up addressing lower order concerns simply because that is what tutees want, and since tutors are instructed not to commander a tutoring session, they merely comply. In short, while tutors’ advice should be a delicate balance between student want and student need with the ultimate goal of developing writing and critical thinking skills, this is hard to achieve especially since detecting and explaining mechanical errors is often an easier task for both tutees and tutors.

Another Challenge: Length of Tutoring Cycle

Another struggle for T. OWL has been providing feedback in what the students and their instructors consider a timely manner. When we asked our participants to share with us the most common complaints on the part of their students, we were not surprised to see a couple of answers about how “It takes too long for feedback.” Considering that tutees can get immediate help when they walk in for a face-to-face session, waiting up to forty-eight hours to hear back from T. OWL may seem excessive. While most papers are reviewed on the same day that they are submitted, at times the tutees have to wait until the next day or even longer when the submission is sent during the weekend. For example, during the fall 2019 semester, 77 submissions were reviewed by an OWL tutor within 24 hours. During the same semester, between our closing time on Friday, November 30, 2019, and Monday, December 3, 2019, we had eleven submissions, with ten coming in after closing hours on Friday and one sent in on Saturday (“OWL Form Fall 2018”). Nine tutees received feedback on Monday, but two had to wait until Tuesday because the tutors scheduled on Monday did not have enough time to finish all OWLs while handling face-to-face sessions as well. Waiting from November 30 to December 3 or 4 may seem extreme, especially as this is close to the final exam week, so it is understandable why that may frustrate both students and instructors. At the same time, while the papers can be submitted at any time online, their handling depends on the physical space of the Learning Center to be open and adequately staffed.

Additionally, the longer wait can occasionally be explained by the challenges posed by technology. The submission guidelines on our website direct the tutees to submit only Microsoft Word and rich text format documents, but that requirement is often overlooked, and the tutors end up with files that they cannot view. This is particularly a problem for CCP students who send us google documents because that is the program provided by their high schools. In such cases, the tutors must contact the tutees to ask for access to the document. Additionally, some of the students fail to enter a working university email address in the online submission form. This adds one more step to the tutoring process as the tutor must then ask the English Coordinator to figure out the student’s correct university email address by searching the directory or contacting the professor. During the fall 2018 semester, for instance, 16 out of 120 submissions were delayed or never reviewed because we did not have the student’s correct information. It seems like our questionnaire participants, however, are aware of these issues; one noted that “Students try to submit the wrong file types and forget that they need to use their [university] email (this is something that I, as the instructor, need to address more carefully). Also, some students forget their [university] credentials and never make the effort to stop in and reset them.” Asking for the students to resubmit and figuring out the correct email address takes time and may contribute to the excessive wait that these students experience.

Conclusions and Recommendations

While we were revising this article, the United States was beginning to see the implementation of the first measures promoting social distancing as a response to the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Our university suspended instruction for three days to allow professors to convert face-to-face instruction to online instruction; for the English tutors in the Learning Center, this transition was seamless because they were prepared. They had been tutoring online for years. They continued to support our tutees from a distance and felt like they were needed more than ever, considering that the students’ access to their instructor and their peers had suddenly changed and, in some instances, may have decreased considerably, as instructors scrambled to learn how to make their Blackboard course more interactive. The OWL submission process remained a constant in a time where everything else seemed to shift in unexpected ways; although the tutors worked from home, the quality and timeliness of their feedback stayed consistent.

Our small study suggests that online peer tutoring is a desirable option for students who find it difficult to travel to campus for face-to-face tutoring even in times when campuses are not threatened by a deadly virus. Online tutoring, though, works best when peer tutors and tutees share the sociocultural characteristics specific to a particular location and ideally are from the same campus. While use of eTutoring may be a good idea for students looking for more perspectives on their writing, their instructors show a clear preference for our campus OWL when they need help with their writing. Campuses should, therefore, invest more in training online peer tutors from their home campus rather than use outside eTutors or no online tutors at all.

Moreover, as online tutoring submissions increase in numbers, small campuses like ours need to change how we allocate resources, so we fairly respond to our students’ needs. Generally, face-to-face tutoring takes precedence over OWLs simply because it is difficult to turn away a student walking into the Learning Center in order to respond to an OWL. Yet, this is unfair to the OWL tutee who is waiting for the email with the tutor’s review. So far, however, we have not been able to find a solution to this problem and reviewing OWL submissions is left for the down time in between face- to-face sessions. Having a designated OWL tutor might help, should the administration be willing to pay for such services remotely. Prior to this semester, our administration understood the need for an OWL tutor, but they insisted that he or she would work from the physical location of the Learning Center. When we tried it, we ran into another problem: the OWL tutor ended up being sucked back into face-to-face tutoring during peak times in order to alleviate long wait times. In a small tutoring center such as hours, making the OWL tutor remote is a must. Moreover, the eight weeks of the spring 2020 semester were proof that the English tutors can effectively perform their OWL duties while off campus; this provides a strong argument in favor of remote tutors that the administration may consider more thoroughly in the future.

Another suggestion is to promote the continuous exchange of information between the Learning Center English Coordinator and instructors who can ensure that their students complete the submission forms and upload the essay drafts and writing prompts in format that peer tutors can access. Regular email messages to faculty and students informing them that submissions submitted late on Friday afternoon will not be read until the following week should also be considered. This same information can be posted on the Learning Center website as an additional reminder that response times may be delayed due to the high volume of online submissions on the weekends, especially during midterms and finals. The Learning Center should also carefully review and revise the OWL submission guidelines, so they clarify and emphasize important procedural information. Additionally, evaluation of tutoring services by students and instructors can help to improve the quality of tutoring provided, particularly if this information is gathered anonymously and with the help of open-ended questions.

Finally, writing and learning centers need to do a better job of documenting what they do. Though it takes time away from directly helping students, there can be real value in writing and learning centers collecting accurate statistics such as the number of online and face- to-face tutoring sessions, the amount of time tutors spend on each session or in an online review of a paper, the peak times for online and face-to-face tutoring, and the number of same-draft submissions. When coupled with data on student retention and withdrawal rates, grades awarded in writing classes, and grade point averages, writing and learning center coordinators can use this type of longitudinal data to demonstrate to administrators the qualitative value of both online and face-to-face tutoring and that similar attention and resources should be devoted to each. It is only through methodical and strategic documentation that writing or learning centers have a chance to receive the funding and staffing that they and their students deserve.

Notes

1. Ana is responsible for tutor training, scheduling, and oversight of English tutors in the campus Learning Center. She also helps to arrange visits to instructors' classrooms to promote Learning Center services. Pam is responsible for scheduling English classes for full-time and part-time instructors on our campus and is a champion of the Learning Center.

WOrks Cited

Carino, Peter. “Power and Authority in Peer Tutoring.” Center Will Hold, edited by Michael A. Pemberton and Joyce Kinkead, University Press of Colorado, 2003, pp. 96-113, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46nxnq.9

Cho, Kwangsu et al. “Validity and Reliability of Scaffolded Peer Assessment of Writing from Instructor and Student Perspective.” Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 98, no. 4, 2006, pp. 891- 901, doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.891

Cho, Kwangsu, and Charles MacArthur. “Student Revision with Peer and Expert Reviewing.” Learning and Instruction, vol. 20, no. 4, 2010, pp. 328-338, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.006.

“Enrollment Report.” Institutional Research, Kent State University. https://www.kent.edu/ir. 10 Oct. 2019.

“eTutoring.” Ohio Department of Higher Education. www.ohiohighered.org/students/prepareforcollege/etutoring. Accessed 7 Oct. 2019.

“Facts & Figures.” www.kent.edu/trumbull/factsfigures. Accessed 18 May 2020.

Gotti, Stephanie, et al. “Overcoming Challenges in Online Peer Tutoring.” Annual Showcase for Student Research, Scholarship & Creativity. 6 Apr. 2015. Kent State University at Trumbull. Student paper, https://oaks.kent.edu/trumbull_showcase/2016/ Posters/5

Jesnek, Lindsey M. “Peer Editing in the 21st Century College Classroom: Do Beginning Composition Students Truly Read the Benefits?” Journal of College Teaching & Learning, vo. 8, no. 5, 2011, pp. 17-24, https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v8i5.45257

“Learning Center Employment.” Learning Center, Kent State University at Trumbull. https://www.kent.edu/T./learning-center- employment. Accessed 29 Sept. 2019.

Linken, Sheri, and John Russo. “With GM Job Cuts, Youngstown Faces a New ‘Black Monday.’” CityLab, 27 Nov. 2018 .www.citylab.com/perspective/2018/11/lordstown-gm-plant-closing-youngstown-ohio-autoworkers- jobs/576775. Accessed 17 May 2020.

McLukie, Joseph, and Keith Topping. “Transferable Skills for Online Peer Learning.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 29, no. 5, 2004, pp. 563-584, https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930410001689144.

Ohio Department of Education. “Warren City District Grade.” Ohio School Report Cards. www.reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/over view/044990. Accessed 17 May 2020.

---. “Youngstown City Schools Academic Recovery Plan.” www.education.ohio.gov/Topics/District-and-School-Continuous- Improvement/Academic-Distress- Commission/Youngstown-City-Schools-Academic-Recovery-Plan. Accessed 17 May 2020.

“Ohio Launches Nation’s Largest Free Online Tutoring Network.” Ohio Higher Education. https://www.ohiohighered.org/node/1734. Accessed 7 Oct. 2019.

“OWL Submissions Report.” Internal report. Learning Center, Kent State University at Trumbull. 10 Oct. 2019.

“OWL Form Fall 2018.” Internal Report. Learning Center, Kent State University at Trumbull. 10 Oct. 2019.

Pfrenger, Wendy et al. “At First It Was Annoying”: Results from Requiring Writers in Developmental Courses to Visit the Writing Center.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 15, no. 1, 2017, pp. 22- 35.

Raymond, Laurel and Zarah Quinn. “What a Writer Wants: Assessing Fulfillment of Student Goals in Writing Center Tutoring Sessions.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, 2012, pp. 64-77, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442382.

“Schedule of Classes.” Kent State University, English 11011 and English 21011, online sections only, fall 2019.

Smith, Jeanne. “Re: Chat Feature Data?” Received by Pam Lieske, 30 Sept. 2019.

Topping, Keith J. “Methodological Quandaries in Studying Process and Outcomes in Peer Assessment.” Learning and Instruction, vol. 20, 2010, pp. 339-343, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08003

U.S. Census Bureau. “QuickFacts, Warren City, Ohio.” www.census.gov/quickfacts/warrencityohio. Accessed 27 Sept. 2019.

Wurtz, Keith A. “Impact of Learning Assistance Center Utilization on Success.” Journal of Developmental Education, vol. 36, no. 3, spring 2015, pp. 2-10, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/246141018

Appendix A

Table 1. Data provided by Institutional Research (“Enrollment Report”)

Chart 1. Q5 - Areas in which you are struggling/ What do you need help with? (click all of the boxes that apply)

Data from “Owl Submissions Report”

Appendix B

KSU T.

ENG 01001 Intro Stretch

Portfolio Grading Rubric

Section and student number ____________

Student’s instructor ____________

In order to pass the portfolio, two of the three essays must earn a YES score for each of the following questions. If the question is not applicable, cross out YES/NO and write NA.

Does the essay answer the prompt, and does it meet basic requirements, such as length and use of sources, as detailed in the prompt?

Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

Is the thesis an arguable claim—no fact, strategy language, or rhetorical question—and

does it sit at the end of the introduction or first paragraph?Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

Does the essay consistently support the thesis? Answer YES if the essay’s thesis is supported 50% of the time or more.

Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

Does the essay contain evidence, such as specific examples and thoughtful explanation, to support the thesis or topic sentences?

Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

Is there a clear distinction between introduction, body, and conclusion?

Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

Are more than ¾ of paragraphs unified and developed and make one point that supports the thesis?

Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

Does the essay's organization make sense?

Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

Does the essay adhere to MLA formatting and rules for in-text and end-text citations?

Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

If quotations, paraphrases, or summaries are used in the essay, are they well integrated? If quotes are just plopped down, or sources appear out of nowhere, answer NO.

Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

Are grammatical, punctuation, and word choice errors kept to a minimum? Can readers still understand the essay's train of thought, or are the errors too distracting or annoying? (If more than ½ of the essay is hard to understand, answer NO)

Essay 1 YES NO Essay 2 YES NO Essay 3 YES NO

Portfolio assessment: PASS or NOT PASS (circle one)

Brief comments:

Appendix c

Online Tutoring

Thank you for participating in this anonymous survey. The goal is to understand how effective our tutoring services are and what we can do to improve them. The first few questions are designed to collect demographic information, and the rest of the survey is about eTutoring and the online submission service/ online writing lab (OWL) within the Learning Center at Kent State University at Trumbull.

How many years have you taught courses for Kent State University at Trumbull?

☐ 1 year or less

☐ 2-3 years

☐ 4-6 years

☐ 7-9 years

☐ over 10 years

Which of the following courses have you taught? You can check more than one box:

☐ English 01001 Intro to Stretch

☐ English 11002 Stretch I

☐ English 11011

☐ English 21011

Where do your college courses take place? You can check more than one box:

☐ In a high school

☐ On the Kent State at Trumbull campus

☐ Online

Do you require or recommend tutoring to your writing students?

☐ Require

☐ Recommend

☐ Neither

Which type(s) of tutoring do you require or recommend?

☐ Face to face (F2F)

☐ Online

☐ Other ____________________

What percentage of your students (current and prior) submit their papers to the Trumbull OWL?

☐ 0%

☐ Up to 25%

☐Up to 50%

☐ Almost all students

☐ Other ____________________

What percentage of your students (current and prior) submit their papers to eTutoring?

☐ 0%

☐ Up to 25%

☐Up to 50%

☐ Almost all students

☐ Other ____________________

In general, what are you likely to recommend to your students for peer review when they write a paper? You can check more than one box:

☐ Review with a peer taking the same course

☐ Review with a family member or friend

☐Review with an English tutor during a face-to-face (F2F) tutoring session

☐ Review with an English tutor during an online asynchronous tutoring session

☐ Other ____________________

What do your students seem to prefer: face to face or online asynchronous tutoring?

☐ Face to face

☐ Online eTutoring

☐ Online Trumbull OWL

What do YOU generally expect Trumbull OWL tutors to address in an online tutoring session?

What are the top 3 student comments about using online Trumbull OWL tutoring?

What are some of the benefits and problems that your students have reported with using online Trumbull OWL tutoring?

What are some of the benefits and problems that YOU have noticed with your students' using online Trumbull OWL tutoring?

Please suggest 2 ways to improve your students' online tutoring experience with Trumbull OWL.