Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 13, No. 2 (2016)

ARE OUR WORKSHOPS WORKING? ASSESSING ASSESSMENT AS RESEARCH

Justin B. Hopkins

Franklin & Marshall College

justin.hopkins@fandm.edu

I’m not alone when I say I’ve spent time grappling with assessment. The final issue of Writing Lab Newsletter includes a series of reflections on the topic, responding specifically to Neil Lerner’s seminal 1997 article on assessment, “Counting Beans and Making Beans Count.” Even more pertinent to my purposes is Holly Ryan and Danielle Kane’s contribution to Writing Center Journal, “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Writing Center Classroom Visits: An Evidence-Based Approach.” Similar to Ryan and Kane, I’ve been evaluating writing center classroom visits. More specifically, I’ve been evaluating Franklin and Marshall College’s writing center’s in-class workshop program. Ten years ago, we began offering workshops on topics with which faculty members felt their students struggled, ranging from higher-order, macro-concerns like constructing a strong thesis statement to lower-order, micro-concerns like correctly using commas. Now I direct the program, preparing presentations with examples and exercises, and turning the materials over to the Center’s undergraduate tutors, who lead the sessions.

Guiding Questions

I feel fairly confident of the program’s overall success just by looking at some simple numbers. In 2015/16, faculty requested over 170 in-class writing workshops, compared to sixty-five in 2005/06, the first full year of the program. We’ve more than doubled our output in a decade, which means we must be doing something right. But what, precisely? More important, how might we yet improve the service? Ellen Schendel and William J. Macauley, Jr. insist in Building Writing Center Assessments that Matter, “Good assessment drives positive change” (xx). We want positive change, so how can we demonstrate our accomplishments while still soliciting constructive criticism to achieve that change? Simply put, how do we use assessment to get better?

Ideally, we would run an extensive experiment, empirically demonstrating that the workshops dramatically improve students’ actual writing skills, but such a study would prove too big a bite to chew at the moment. However, we can evaluate the impact of the workshops more generally, and still usefully. Did the students think and feel the workshops were worthwhile, and if so, how and why, and if not, how and why not? And again, what can we do to improve? The most obvious way to answer those questions is to ask those who participate in the workshops what works and what doesn’t. We’ve done that. But I’m not convinced we’ve always done that as well as we could. Hence this essay, in which I’ll explore the evolution of our student evaluation form and, in particular, how the different versions of the form have navigated the channel between qualitative and quantitative assessment, as well as showing how my project reflects bigger issues regarding assessment and research.

Dichotomy?

I will examine how assessment relates to research. In their recent Researching the Writing Center, Rebecca Day Babcock and Terese Thonus draw a definite distinction between the two practices, though they note, “assessment can easily pave the way to research” (5). They also acknowledge that research and assessment share such key characteristics as a common goal—inquiry and scholarly problem-solving—and methods of data collection (4). Given Babcock and Thonus’s insistence on a separation of terms alongside observations of their similarities, I remain confused, and a bit concerned, about how to discern the dividing line.

Apparently, according to Dana Lynn Driscoll and Sherry Wynn Perdue’s even more recent “RAD Research as a Framework for Writing Center Inquiry,” I’m not alone in my uncertainty. Their study of Writing Center Administrators reveals a considerable lack of consensus when it comes to distinguishing the two phenomena: 18% of those surveyed indicated “Research is assessment” (113), and one interviewee, Dara, went further: “Research is assessment; assessment is research” (118). With these perspectives proliferating, perhaps it is no surprise that my other guiding questions in this essay include: what is the difference between research and assessment, and which am I performing?

Definitions

For now, I will continue with the assumption that I am involved in research, based on an Oxford English Dictionary definition: “Systematic investigation or inquiry aimed at contributing to knowledge of a theory, topic, etc., by careful consideration, observation, or study of a subject” (2a). I claim that my consideration was careful and my investigation systematic, and it is certainly “presented in written (esp. published) form” (2c). On the other hand, to support their contention (and relying on the American Heritage Dictionary rather than the OED), Babcock and Thonus provide a comparative etymological breakdown of the words “assess” and “research” and interpret their findings: “Research, then, does not necessarily involve evaluation or judgment” (4, emphasis mine). Fair enough. But must research by nature reject evaluation? I find nothing in the OED (or their reading of the AHD, for that matter) to preclude the possibility of research involving judgment.

Furthermore, Babcock and Thonus conclude, “Nor does [research] seek immediate application to a local context; rather, it opens inquiry beyond the local context (the individual writing center) to global contexts and applications” (4). Again, I see no reason research must refrain from engagement with the local, though I certainly acknowledge the value of its connection with the global. I will return to this issue after describing my project because the automatic assumption of research as exclusively global (and greater in value?) and assessment as local (and lesser in value?) concerns me. Along the way, I request that the reader reflect on whether or not and how the assessment project I describe conforms to his or her, Babcock and Thonus’s, Driscoll and Perdue’s, Dara’s, the OED’s, the AHD’s, or any other definition of research.

Methodological Approach

My methodological approach, as mentioned above, included collecting both quantitative and qualitative data. Though there is a history of tension, if not of conflict, between these methods (see Doug Enders’s “Assessing the Writing Center” and Cindy Johanek’s Composing Research), the two can certainly and comfortably coexist. In an interchapter contributed to Schendel and Macauley’s book, longtime assessment scholar Neal Lerner explains the subtleties of the separate strategies and ultimately reminds us, “qualitative and quantitative research need not be mutually exclusive (or hostile camps)” (112). Rather than picking one side, or pitting the two against each other, we should—and I have tried to—approach research/assessment from both angles.

First Attempt at Assessment

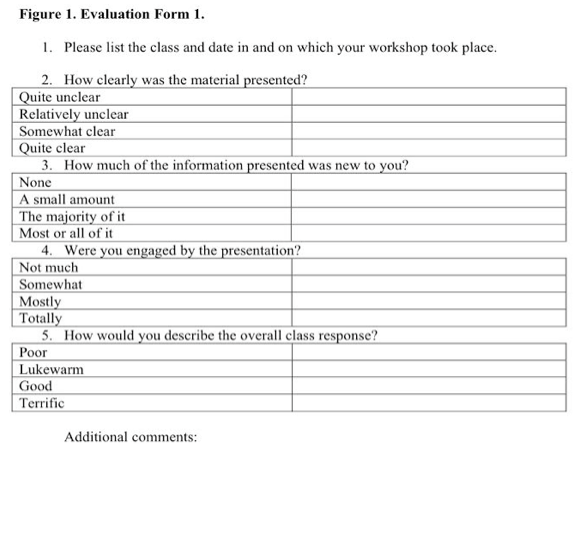

Any assessment is better than what our workshop program started with, which was nothing more than the simplest tally. Merely counting did show good things happening. By the end of 2006/07, the number of workshops had risen to just under one hundred—a growth of 50%. However, as happily as we watched the numbers climb, we knew, as Schendel and Macauley observe (paraphrasing Isabelle Thompson), “counting visits simply won’t be enough” (13). We welcomed, therefore, the administration’s request for more detailed assessment procedures. We designed a feedback form (Figure 1) that tutors distributed at the end of each workshop. The form asked students four questions regarding what I’ll call clarity, novelty, engagement, and response. Students could answer each question on a 4-point scale: quite negative, somewhat negative, somewhat positive, extremely positive. Clearly, quantitative questions dominated the form, but we solicited qualitative responses too, by prompting students to provide “Additional comments” below or on the back of the half-sheet of paper. This is the form we used for four semesters: Fall 2007, Spring 2009, and academic year 2010-2011. (The several semesters un-assessed were due to changing leadership models, during which evaluation went by the wayside.)

Table 1 shows our quantitative results. Clarity consistently scored the highest, with less than 10% marking less than a 3 in any given period. Novelty scored much lower, with at least 75% marking less than a 3 each period. Engagement and response were more balanced, marked mostly with 2s and 3s, though both categories noticeably improved from 2007 to 2011/12. From these numbers I could conclude the workshops clearly presented material with which students (thought they) were already familiar, with which they were moderately engaged, and to which they might respond, “meh.”

Comments on the First Form

Actually, they did respond more articulately, if not always less ambiguously. Over the three years, we received additional comments on an average of about 22% of the forms returned. These comments ranged widely in usefulness. About half contained praise. Praise is nice. But does it help? Schendel and Macauley say maybe not:

Many WCDs use satisfaction surveys, and when the data comes back consistently high, the[y] accept that their centers are succeeding. However, these kinds of results, though useful and appreciated, don’t allow the directors to continue to develop the writing center from those data. (20).

I was happy to pass along compliments like “Judith is awesome! She should just teach the class because of her vitality and [British] accent!” But these kind words did not concretely benefit either Judith or the program. On the other hand, neither did unconstructive criticism like “Condescendingly trivial information. Please teach at a level relevant to college students.” We know we often enter classes that include different levels of development, and we try to present ideas that can challenge and support everyone, but we also know that some seniors don’t need what some first-years do, and there’s not a lot we can do about that. (Then again, some seniors might need more than they think they do, and some students surveyed gratefully acknowledge the pedagogical usefulness of repetition: “Good reinforcements of ideas that had already been taught but never put to use.”)

Some comments confirmed the philosophy behind the program and undergraduate tutoring in general. Our center operates on the assumption that students value peer (in addition to professional) support, and when we hear “I liked that they related the points to their own writing—one of the perks of having students help students” we can reaffirm our approach. Perhaps best of all, we often read some variation of “I’ll definitely make an appointment” meaning we’re achieving one of the workshop program’s main goals: encouraging students to visit the center.

However, even more useful was the constructive criticism we occasionally found. We welcomed complaints that led to improvement. For instance, we were informed our examples were “fantastically boring. Please pick an example essay about something a bit more exhilarating than transcendentalism.” So we threw that essay out. We were discouraged from flat delivery: “It is hard to engage students by just reading from a packet of handouts.” So we worked harder training tutors to interact more with the audience. We were chided for rushing: “Slow down on the slides; taking notes was not feasible.” So we told tutors to take their time, talking at a reasonable pace.

Second Attempt at Assessment

These suggestions were invaluable, but by the end of spring semester 2012, I realized I just wasn’t satisfied with the form. Some of the numbers seemed redundant. Did we need to measure both engagement and response? And why waste space measuring novelty when we knew the majority of students would score it negatively? Also, the balance between qualitative and quantitative reporting was off: there simply were not enough stories.

I decided to put together a new form (Figure 2), fulfilling Schendel and Mcauley’s exhortation: “who wants to do assessment that is not as useful as it can be?” (20). I wanted to keep some numbers, but I condensed quantitative response to just two questions reflecting clarity and engagement, following a five-point Likert scale. Two new questions required written, qualitative replies. The first asked students to compare the workshop to others they may have participated in. The second asked if students would want to participate in another workshop in the future.

Table 2 shows the new form’s quantitative results for 2012/13. Clarity remained high, with over 97% marking a 4 or a 5. Likewise engagement, with less than 5% marking a 1 or a 2. Over 70% said yes, they would like to attend another workshop, and of those who said no or maybe, many indicated that their reluctance was due to lack of time, not interest. These were good—both positive and useful—numbers.

comments on the second form

But what about the qualitative results? With nearly every form offering some kind of story, what do we learn from them? Some comments were inscrutable: “Learning writing in a class is more rhythmical than from books.” Some were positively impertinent: “Writing Center helpers are attractive.” Some were belligerent and rude: “No. I know how to write. I passed the 3rd grade.” A few were over-the-top enthusiastic: “Yes Yes Yes!!!!! I never learned how to formally write in high school—thank you. Please more!!!!” Gratifying, grating, irritating, or incomprehensible, none of these narratives proves particularly useful.

As hoped, however, some specific suggestions revealed real (and familiar) needs. We still needed to slow down: “The only thing I didn’t like was how fast we went through each exercise.” We still needed more interaction: “It helped, but it could have been more useful to look at other student’s writing to see how to improve it.” We still needed fresh examples: “Example for thesis statement about Catholicism is used again!?”

Some comments cast welcome, albeit conflicting, light on a particular aspect of the program. For example, we were (and are) experimenting with workshops without PowerPoint presentations, depending more on handouts and discussion. Feedback on this issue split fairly evenly. Some liked it: “Most [workshops] have boring powerpoints. Using a good interesting [sic] paper [to guide discussion] was a good choice and kept me engaged.” Some did not: “I liked the power point workshops better. It got people way more engaged.” On another occasion, comments conflicted regarding a session in which we used magazine articles to demonstrate the effect of strong openings lines. “Good magazine exercise” congratulated one. Another retorted: “I found the magazines distracting.” Apparently the cliché is correct: you can’t please all of the people all of the time.

Third Attempt at Assessment

For my part, I was not completely pleased with the new forms. I did like the consolidation of the quantitative reporting, and I did value the additional comments, though they took an awful lot longer to process thoroughly. In “Approaching Assessment as if It Matters” Jean Hawthorne warns, “it’s important to do more than browse through the data and pull out interesting but anecdotal examples” (243), and with so many anecdotes, that temptation was certainly strong. Furthermore, while I certainly didn’t think the comments were any less useful, I also didn’t think they were that much more useful than those from previous years.

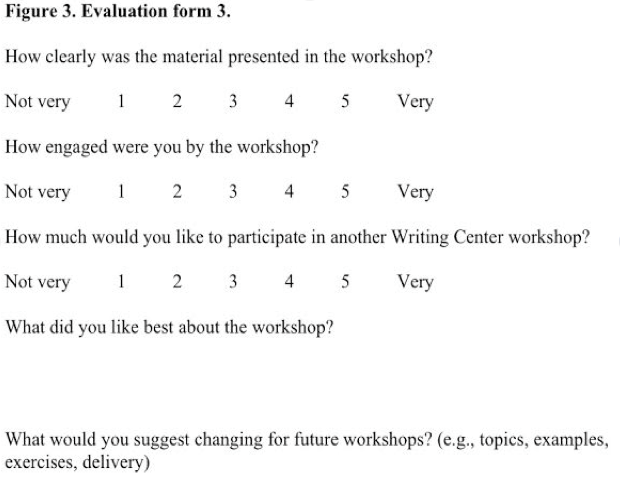

Another round of revising the forms seemed necessary. After presenting my assessment project at MAWCA 2013, and having received excellent recommendations, I made several changes (Figure 3). I adapted the “Yes/No” binary options of whether or not students would want to participate in another workshop into a Likert scale, leaving room for more direct questions as to what was working and what was not.

Table 3 shows how little the numbers have changed from the previous year. Clarity has changed barely at all. Slightly more people remain neutral when it comes to engagement, 5% more marking a 3. For the most part, people still wanted to participate in another workshop, over 65% marking a 4 or a 5. Given the relative consistency of the numerical results, it seems safe to say we stand on increasingly solid ground, quantitatively.

Comments on the Third Form

Qualitatively, we seem to be finding our feet as well, as we find that, finally, the stories students tell are more useful than not. While randomly selecting the forms from one workshop, sure, we will still hear the occasional impertinent catcall: “[one of the presenting tutors] should pop out of a cake!” However, the majority of the sample gives good, helpful feedback. In answer to the question about what works best, we know that “the delivery” stands out—a common theme, echoed by several: “She was very friendly” and “Loved her enthusiasm,” plus three mentions of how “straightforward” everything was. When it come to suggesting changes, some said, “Nothing” or “not much,” but others said “More examples” or “more individual time with the presenter.” Two called for shorter overall sessions, and three others for improvements to our PowerPoint presentations. And this is only a small selection of the roughly one thousand (very) short stories told in this year’s comment forms. With the combination of questions explicitly identifying our strengths and directly requesting recommendations for improvement, we may have finally hit on an ideal assessment tool. To me, at least, it is a satisfactory one with which to proceed. It seems appropriate to close this section with a comment answering the survey question of whether or not the student would like to participate in another workshop: “It would appear as though I cannot avoid them” followed by an emoticon—😀—and parenthetical explanation: “(But I do always learn, so yes.)” Our workshop program isn’t going away, and neither is the need for assessment. Where exactly we do go with the workshops, and how we get there, depends on the assessment we perform.

Back to Definitions

But what of Babcock and Thonus’s fine line between research and assessment? Which have I been doing all this while? I am reminded of Driscoll and Perdue’s initial championing of RAD (replicable, aggregable, and data-driven) research as opposed to “little more than anecdotal evidence, one person’s experience” (“Theory” 16). Is the latter all that this project represents? I hope not. I collected a lot of data, and I imagine others could replicate and aggregate the study, at least to some extent, adapting my methods and building on my findings. But perhaps I’m among the many who don’t fully understand, much less rigorously apply, the RAD model (Driscoll and Perdue “RAD Research” 123-125)? I’m convinced our assessment is no longer bad, but is it really RAD research? Babcock and Thonus would probably say no, arguing, “what [Muriel] Harris described as local research is better termed assessment” (4), but I’m not so sure of the sharp distinction. I tend to take Harris’s term more for face value: maybe research and assessment should not be differentiated so definitely. I have suggested that my project is both, but I leave that to the reader’s judgment.

However, I remain concerned by what seems an attempt to remove writing center research from the realm of the local. Yes, we need more research, ideally including RAD, but does that paradigm threaten to overwhelm what has arguably worked for writing centers for a long time, and what might continue to work if we let it? I am speaking, of course, of lore. I realize that the analogy is not perfect, but I perceive a relationship between lore and local assessment, just as I (and others) perceive a relationship between data and global research. For example, Roberta Kjesrud, in her Writing Center Journal article “Lessons from Data: Avoiding Lore Bias in Research Paradigms,” pits Lore against Data, showing how limited and limiting the former can be: “I am now silencing Lore to let Data speak” (40). I take the lesson, but why must we set the two against each so antagonistically? It is a binary battle even Kjesrud “so wish[es] to avoid” (40), yet she engages in it all the same, and with results potentially if not probably damaging to Lore’s reputation. Surely difference need not lead to disagreement and destruction of one or the other? Just as qualitative and quantitative methodologies are compatible, surely local Lore (and assessment) and global Data (and research) can coexist, cooperate, and even collaborate, even if they aren’t the same to begin with?

Dichotomous Coexistence?

Some say no. Granted, Kjesrud attempts to soften her criticism of Lore: “Lore isn’t a villain. As a community of practice, we value our Lore for good reasons” (51). True, Driscoll and Perdue “stress that by conducting RAD research in writing centers, we are…not devaluing other paradigms and frameworks that have served and will continue to serve the WC community” (“RAD Research” 107). But I fear Kjesrud and Driscoll and Perdue’s and others’ arguments might have just that effect, eliminating or at least marginalizing lore and the local (and assessment). For example, Driscoll and Perdue urge moving beyond the local “Uniqueness” factor that seemingly hinders RAD research, insisting that contrary to popular perception, “a great deal of similarity exists in the practices and procedures of [writing] centers” and recommending that research focus on the similarities rather than the differences (“RAD Research” 121). I might balk at this notion—do the similarities outweigh the differences between individual writing centers’ practices and procedures?—but even if I did concede, they further differentiate between “Unique Assessment Data” and “Reconceptualiz[ed] ‘Local’ Data.” The first they indicate is genuinely local (associated with assessment), the second more global (i.e., research). Then they assert, “not all data are created equally” and their preference for the latter is plain (“RAD Research” 122). And they are not alone in that preference.

I do not disparage Kjesrud’s, Driscoll and Perdue’s, and Babcock and Thonus’s, and others’ efforts to bring writing center research into a bigger, more global conversation. I applaud those efforts, and I have made an effort to conform to RAD standards in my own assessment project. Yet I still believe there remains an important place for a focus on the local in writing center research, as in writing center assessment. In a (global) world increasingly dominated by data, embracing RAD research without reservation risks reducing the local to “just” lore (or assessment)—un(der)appreciated, and un(der)used.

Let me provide an example to illustrate my point. I return to my initial comparison of my project with Ryan and Kane’s, which is presented as (RAD?) research. I have no wish at all to detract from their accomplishment—their study is admirable—but I must point out that in their “Limitations” section, they acknowledge one of the challenges facing many if not any writing center researchers wanting to conduct (RAD) research: “other types of institutions may experience different dynamics” (162). Despite Driscoll and Perdue’s assertion to the contrary (“RAD Research” 121), I suspect dynamics at other institutions of any type most likely differ quite a bit, which indeed limits the claims of universality for much, if not at all writing center research. Once more, I do not intend to reject RAD research, merely to challenge some of its assumptions, and to defend the kind of local lore that some would say is typical of assessment.

Doing Our Best

Rather than debate about binaries, though, maybe we had better just do what Scott Pleasant suggests in his Writing Lab Newsletter article, “It’s Not Just Beans Anymore; It’s Our Bread and Butter.” Pleasant reviews Neal Lerner’s work, describes his own assessment project, and offers advice for others: embrace the scientific method; work with experts whose knowledge can supplement your own; trust the data; and fit your project to the local assumptions about assessment (10-11). Pleasant does distinguish between “writing center quantitative assessment or research” (11), but his emphasis throughout is on doing (whatever you call) what you’re doing well, rigorously, scientifically. I am convinced that such an approach to assessment elevates it to the level of research, even if it is not there to begin with.

In closing, I remember Neal Lerner’s advice about assessment in “Choosing Beans Wisely.” For me, the key to counting the right beans is his phrase “on our own terms” (1). (Frances Crawford calls Lerner’s advice “timeless and still relevant today” and insists, “We can and should use assessment to define what we are” [12].) Much as we all may want to conduct RAD research, much as we all want to contribute to the larger writing center community, must we not keep returning to the goal of local positive change in our own centers? Really, I suspect, more than an attempt at the comprehensive and global, much less the universal, what we actually crave at the most practical level is truly constructive assessment—assessment for us, not just of us.

Figures

Works Cited

Babcock, Rebecca Day and Terese Thonus. Researching the Writing Center. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., 2012. Print.

Crawford, Frances. “Reflection on Lerner’s Bean Counting.” Writing Lab Newsletter 39.9-10 (2015): 12. Print.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Sherry Wynn Perdue. “RAD Research as a Framework for Writing Center Inquiry: Survey and Interview Data on Writing Center Administrators’ Beliefs about Research and Research Practices.” Writing Center Journal 34.1 (2014): 105-134. Print.

---. “Theory, Lore, and More: An Analysis of RAD Research in Writing Center Journal, 1980-2009.” Writing Center Journal 32.2 (2012): 11-39. Print.

Enders, Doug. “Assessing the Writing Center: A Qualitative Tale of a Quantitative Study.” Writing Lab Newsletter 29.10 (2005): 6-9. Print.

Hawthorne, Jean. “Approaching Assessment as if It Matters.” The Writing Center Director’s Resource Book. Ed. Christina Murphy and Byron L. Stay. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 2006. Print.

Johanek, Cindy. Composing Research: A Contextualist Paradigm for Rhetoric and Composition. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2000. Print.

Kjesrud, Roberta D. “Lessons from Data: Avoiding Lore Bias in Research Paradigms.” Writing Center Journal 34.2 (2015): 33-58. Print.

Lerner, Neal. “Choosing Beans Wisely.” Writing Lab Newsletter 26.1 (2001): 1-5. Print.

---. “Of Numbers and Stories: Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment Research in the Writing Center.” Building Writing Center Assessments that Matter. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2012. 108-114. Print.

Pleasant, Scott. “It’s Not Just Beans Anymore; It’s Our Bread and Butter.” Writing Lab Newsletter 39.9-10 (2015): 7-11. Print.

“Research.” Oxford English Dictionary Online Edition. 2015. Web.

Ryan, Holly and Danielle Kane. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Writing Center Classroom Visits: An Evidence-Based Approach." Writing Center Journal 34.2 (2015): 145-172. Print.

Schendel, Ellen and William J. Macauley, Jr. Building Writing Center Assessments that Matter. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2012. Print.